Root cause analysis

Root cause analysis is a process for understanding 'what happened' and solving a problem through looking back and drilling down to find out 'why it happened' in the first place. Then, looking to rectify the issue(s) so that it does not happen again, or reduce the likelihood that it will happen again.

This guidance provides an overview of root cause analysis and how internal auditors can use the techniques, along with some examples.

What is root cause analysis?

Who uses root cause analysis and why?

Why root cause analysis is of interest to internal audit

What are the benefits of root cause analysis for internal audit?

How and when root cause analysis might be applicable

What are the potential issues for internal audit applying root cause analysis?

What root cause analysis techniques are there and where do they come from?

The five whys?

Ishikawa diagram (fishbone)

Logic tree

Failure mode effects analysis (FME)

Fault tree analysis

Conclusions

Report templates and generic set of root causes

What is root cause analysis?

The three basic types of causes of a problem are physical, human and organisational e.g. a material item failed, someone made an error, a system, process or policy is faulty. Most problems in complex systems are made up of more than one single cause. A range of approaches, tools and techniques can be used to help identify the issues.

Definitions

'A root cause is a factor that caused a non-conformance and should be permanently eliminated through process improvement. Root cause analysis is a collective term that describes a wide range of approaches, tools, and techniques used to uncover causes of problems.' Source: American Society of Quality

'Identification and evaluation of the reason for non-conformance, an undesirable condition, or a problem which (when solved) restores the status quo.' Source: Business dictionary

Who uses root cause analysis and why?

There are a wide range of industries using root cause analysis that includes healthcare, manufacturing, transportation, construction, chemical, petroleum and power.

It may be used to assist in any situation where there is a gap between actual and desired performance, recurring errors or failures with specific processes and undesirable events reoccurring.

It can be used in areas such as quality control, change management, health and safety, business process improvement, operations and project management to name but a few.

Why root cause analysis is of interest to internal audit

Poor organisational culture has been identified as the root cause of problems in a number of different business sectors which has resulted in great cost to organisations. Paying attention to culture and behaviours within internal audits is an important step forward for our profession, more detail can be found on this within the guidance on auditing culture.

In particular internal audit can help the board understand how the organisation’s culture is embedded in a way that affects behaviour throughout the organisation through identifying what needs to be done differently or better. However, poor organisational culture is not a root cause in its own right, cultural issues are caused by a range of organisational, process and behavioural factors.

Internal audit has a role to play in supporting the board and senior executives, be seen to be adding value to the organisation and raising the profile of the internal audit function. Given internal audits overview of the organisation they are in an ideal position to identify any potential themes developing, behaviours that influence decisions, etc.

By applying root cause analysis internal audit reports can be streamlined with higher impact recommendations that are more meaningful to management, reduce risks, add insights that improve the longer term effectiveness and efficiency and performance of business processes as well as the overall governance, risk and control environment, refer to Practice advisory 2320-2 on root cause analysis (RCA).

This will not only provide a better understanding and more in depth learning for internal auditors on particular systems and processes but also the users of these systems. However, to do this auditors will need to have the required skills and experience to perform such work , undertake training, seek outside assistance or recommend in the internal audit report that management perform root cause analysis.

What are the benefits of root cause analysis?

- Internal audit can be seen to be adding value to the organisation

- There is the potential for cost reduction

- Providing a learning process for better understanding of relationships, causes and effect and solutions

- Provides a logical approach to problem solving using data that already exists

- Reduces risk

- Prevention of recurring failures

- Improved performance

- Leads to more robust systems

- Streamlining of audit reporting.

How and when root cause analysis might be applicable

The following provides a list of frequently asked questions and answers on root cause analysis.

1. At what point in the audit process would you consider applying RCA?

- If you’re undertaking an audit that has been carried out previously and the same issues are cropping up then it may be worth spending time undertaking RCA

- Where an assignment is to formally investigate an incident

- At the scoping meeting the manager may raise issues of on-going problems that require attention/ risks that are not being managed. Rather than approach this through standard testing , audit can gather data to determine what the underlying causes are and then include this in the report confirming what the manager has already said

- During one-to-one supervisory meeting of the auditor and audit manager or team meetings

- Through the audit testing you may identify a large number of actions/recommendations that are linked in terms of root causes, allowing for combined findings

- At the debriefing stage of the audit prior to the drafting of the audit report or it may be that a follow-up up audit is carried out using RCA techniques

- The Head of internal audit or audit manager may find a pattern developing over a range of completed audits that warrants an audit on a particular topic/area/department

- When reporting to audit committee, analyse the overall trend of findings that internal audit are reporting on

2. How do you determine which situations to apply RCA to?

The time to use root cause analysis is where there has been a significant event, for repetitive errors and where there is poor performance or where there is no or limited assurance given on an audit.

3. Who would be involved in the RCA?

Of course, line management (first line or defence) or other functions (second line of defence) should carry out root cause as part of business as usual and this should always be considered (or supported) in the first instance. However where internal audit can add value could be:

- By carrying out separate interviews with the manager and each of the staff within the department under review

- By facilitating a meeting of the manager and staff within the department

- By the internal audit department using part of their staff meetings or one-to-ones with the audit manager to consider the issues.

4. How long does it take and how much time needs to be built into the audit plan/audit assignment for this?

This does not have to add a significant amount of time to the audit and may in fact replace some testing. A discussion needs to take place with the audit manager to decide on the way forward.

5. How will this impact on audit reports?

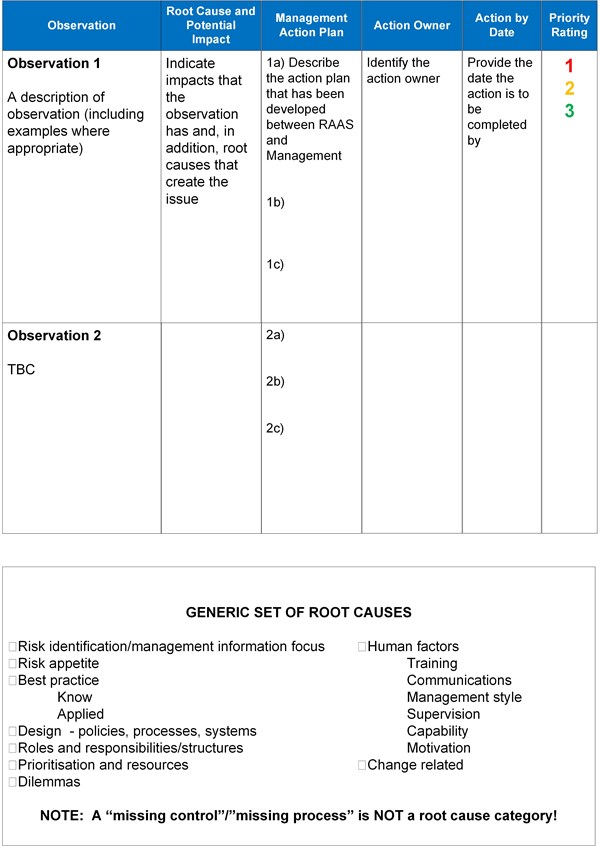

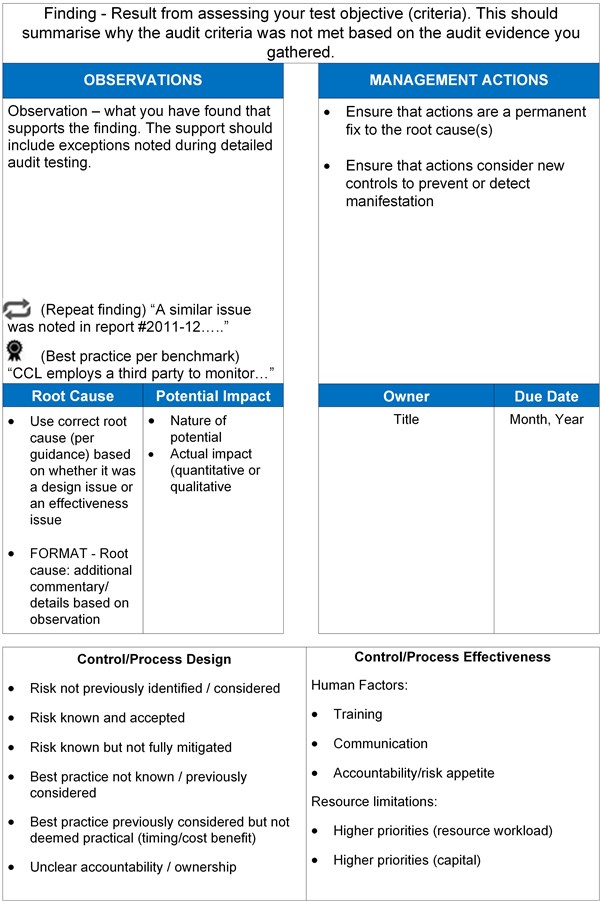

Before getting to the draft report stage discussions need to take place about undertaking root cause analysis. This will save time on writing/re-writing the report and likely to reduce the number of findings. At the end of this guidance some examples are provided of a reporting template and generic set of root causes.

6. The culture of the organisation is a barrier to using RCA what can I do to make them more receptive to using this form of analysis?

- Discuss this at the audit committee meeting and get buy-in from them and include it within the Audit Charter.

- Try using RCA in departments that are more responsive to change and then publicise the results/benefits that have been gained.

7. We outsource some of our internal audit work, how can we get our partners to undertake RCA?

- As mentioned above, get buy-in from the audit committee.

- Discuss this with your delivery partner.

- Include RCA within your audit manual.

- Embed within your audit process.

8. What model should we use?

There are several models to use (see comments below) but consider your choice based on the assignment you are undertaking and discussion with your head of internal audit/audit manager rather than a favourite technique that might not be right for the job. It may be appropriate to use a combination of approaches.

What are the potential issues for internal audit applying root cause analysis?

The culture of an organisation can sometimes prevent staff getting to the true root cause of the problem:

- Concern that there may be repercussions and sanctions arising from RCA rather than an interest in solving problems.

- Deflecting blame such as blaming the problem on external reasons over which the organisation has no control rather than looking at what wasn’t right in the first place or looking to put contingency plans in place.

- The risk appetite for change, the cost of such change may be significant and therefore deemed that the cheaper solution for instance may be to replace or repair a product as it occurs without considering the wider implications and cost of the decision such as customer loyalty and poor customer feedback.

- Experience and confidence in using RCA techniques.

What root cause analysis techniques are there and where do they come from?

There are a range of tools and techniques that can be used for root cause analysis. Examples of such tools are shown below with background information provided on a selection of the techniques and how to use them.

The five why’s technique was originally developed in the 1930s by the Founder of Toyota Motor Corporation, Sakichi Toyoda. Through the Toyota production system it became popular in the 1970s.

Ishikawa diagrams (also known as fishbone or cause and effect diagrams)

The first basic concept was used in the 1920s but popularised in the 1960s through use in quality management in the Kwasaki shipyards. The diagram was also used to help develop the Mazda Miata car.

Failure mode effects analysis (FME)

Developed in the late 1940s to study the problems of malfunctions in military systems, this was then more fully developed by aerospace and automotive industries.

Fault tree analysis

This was developed in the early 1960s for the US Air Force for use with the Minuteman system by Bell Telephone Laboratories. It was subsequently used by Boeing and adopted by the Aerospace industry in the 1970s. In the 1980s and 90s adopted by Chemical, Robotic and Software industries.

How do you use the models?

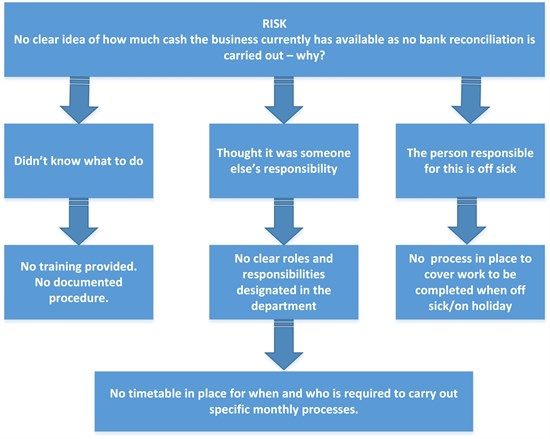

The five whys

Basically it is a case of asking 'why' five times and through each cycle drilling down to identify the root cause. It maybe that you need to ask 'why' more than the five times, but great care should be taken to stop before five questions. Specifically the fact that a solution is available at one level does not mean that the root cause has really been found. When it works well the five why’s should uncover a range of root causes and, therefore, provide all of the realistic solution options.

The five whys is easy to use, useful when problems involve human factors and best for simple to moderately difficult problems with regards to trouble shooting, quality improvements and problem solving. It can also be used alongside other methods.

Example

A complaint is received from a customer as the goods ordered where not delivered on the agreed delivery date.

1. Why were the goods not received on the date agreed?

The company did not have the goods in stock to supply.

2. Why did the company not have the goods in stock to supply?

The product had not been received from the manufacturer before supplies ran out.

3. Why did this happen?

The volume of sales of the product increased significantly over the period.

4. Why was there such an increase in sales of the product?

A marketing campaign had been undertaken and the goods offered at a discounted price.

5. Why weren’t stock levels adjusted to take into account this promotion?

The warehouse was not aware of the promotion and therefore of the change in sales pattern.

Conclusion

One key root cause is the lack of communication between department’s therefore stock economic ordering quantities had not been adjusted to take account of the increase in likely sales. There is normally more than one root cause and a further cause could be that the stock system was not up-to-date; it may be that it is only updated periodically, possibly at the end of each day and appearing to hold stock than is actually is when the system is checked.

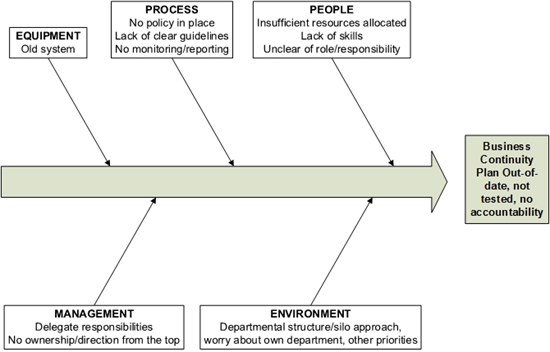

Ishikawa diagram (fishbone)

The Ishikawa model of root cause analysis takes you through a process of first of all describing the problem, collecting and analysing data and then through possibly brainstorming identifying potential causes. This should then enable you to analyse and identify the root cause(s) and then advise on possible solutions. It may take a number of steps to trace the problem back to the ‘root cause’ by going through a series of questions:

- What happened/What was the problem?

- Why did it happen?

- How can it be put right to stop it happening again?

Causes are usually grouped into major categories to identify these sources of variation. The categories typically include those shown in the diagram below.

Example: Problem – business continuity planning

The outcomes from this show that there are a number of problems some cultural and the mind set that this is your problem not mine, just get on with it. This needs to be addressed starting with the board and senior management and the tone at the top through to the need for policies and procedures and training for those involved with business continuity along with updating of systems to ensure efficiency and effectiveness.

Logic tree

A logic tree is a visual problem solving tool that breaks a problem into discrete chunks and helps you search for all the possible causes of a problem through asking questions that lead you to the next level of detail. This can help simplify complex problems and makes it easier for you to get an overview of your options.

Example: Bank reconciliation not carried out

Failure mode effects analysis (FME)

This involves a cross-functional team of people with diverse knowledge about the process, product or service and customer needs, going through and identifying all the ways failure could happen, identifying the consequences and the seriousness of each effect.

For each failure mode the potential root causes are determined. Rating estimates on the probability of failure occurring along with the current controls are recorded as well as the detection rating (this rating estimates how well the controls can detect either the cause or its failure mode after they have happened but before the customer is affected).

Detection is usually rated on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means the control is absolutely certain to detect the problem and 10 means the control is certain not to detect the problem (or no control exists).

Fault tree analysis

Fault tree analysis is a top down approach that is used to help identify potential causes of a system failure before any failures actually take place and then take action to reduce risk on a complex system. It is a graphical model of the pathways within a system that can lead to a foreseeable failure. The process goes through five steps of:

- Define the undesired event to study

- Obtain an understanding of the system

- Construct the fault tree

- Evaluate the fault tree

- Control the hazards identified

Conclusions

- Finding and identifying root causes during an audit adds significant value to the work undertaken by ensuring that the right or most effective action is suggested.

- Managers and employees will gain a better understand of why the problem(s) exist and allow them to put corrective measures in place, ensuring that similar problems do not occur in the future.

- Repeating issues and common themes are a sign that root causes have not been properly addressed.

- Long audit reports with junior action owners may also be symptomatic of poor root cause analysis.

- It is vital that management and second line functions should be encouraged to carry out proper root cause analysis in key areas.

- Internal audit teams should up-skill their approach to root cause analysis since it is a key way to help to change organisational culture.

- Care should be taken when simply thinking there is just one root cause for an audit issue – this is rarely the case.

- Careful thought should also be given to appropriate root cause analysis categories (which is an evolving field that is outside of the scope of this paper).

Report templates and generic set of root causes

Example 1

Example 2